In this post we will continue exploring the world of Win32 shellcode development. You can check here the first part of a series of posts in which we have developed a reverse shell shellcode from scratch.

Today, however, we will try to keep it simpler and swifter. Everything will be done directly withing the debugger, so we can easily get the opcodes and test our shellcode step by step on the fly. Just get any binary, open it in a debugger and overwrite the few first instructions with our shellcode. Also, no more sockets and network related stuff. Let’s see if we really understood the concepts of the previous posts and pop a simple message box.

For that we will need to do the following:

- Get the address of LoadLibraryA in kernel32.dll

- Load user32.dll using LoadLibraryA

- Get the address of MessageBoxA in user32.dll

- Put parameters on the stack

- Call MessageBoxA

Well, actually there is a lot more than that. For instance, take a look at the complete process described at this awesome post:

- Obtain the kernel32.dll base address

- Find the address of GetProcAddress function

- Use GetProcAddress to find the address of LoadLibrary function

- Use LoadLibrary to load a DLL (such as user32.dll)

- Use GetProcAddress to find the address of a function (such as MessageBox)

- Specify the function parameters

- Call the function

This is a way more complete and somewhat more complex workflow. While SecurityCafe’s shellcode is certainly more reliable, our humble code will do the job for a specific system build and version. For the record, I am using a Windows XP SP3. This means the base addresses of some DLLs are not randomized (no ALSR for them), so our hardcoded adresses should work fine for every identical environment.

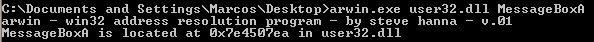

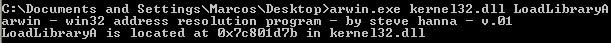

In our case, we will use an external tool to get these fixed address. It is Steve Hanna’s arwin, and you should definetly take a look at it here. Arwin will help us skipping steps 1 to 3 and also step 5. In fact, according to this source:

Why can’t addresses to API functions be hardcoded? Because system API addresses are no longer predictable on modern (post-XP) versions of Windows.

Prior to Microsoft’s release of Vista, Windows loaded system DLLs at hardcoded addresses in all processes. Because each version of the operating system and service pack level happened to load KERNEL32.DLL at the same base address, shellcode could hardcode the addresses for the two “holy-grail” functions (LoadLibrary() and GetProcAddress()) for common versions of Windows and have easy access to the remainder of APIs on the machine. For example, Windows XP Service Pack 3 always loaded KERNEL32 at 0x7C800000, LoadLibrary() at 0x7C801D7B and GetProcAddress() at 0x7C80AE30 system-wide. Besides shellcode needing a table of different addresses per function per version of Windows, it was still pretty convenient to access the system once shellcode gained control.

With the public release of Windows Vista in January 2007, Microsoft stepped up their game with a security feature known as ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization). ASLR randomizes the base load address for all system DLLs including KERNEL32.DLL each time the operating system boots.

Since we are trying to do the quicker and dirtier shellcode possible in a Win XP, we should be fine considering kernel32.dll and LoadLibraryA at the same fixed addresses. Although it might feel like cheating, there is indeeed nothing magical in arwin. It actually is a very simple C code that uses Win32 API to… well, do pretty much the same as what is described in SecurityCafe’s post, but in a higher level language. Take a look by yourself:

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

/***************************************

arwin - win32 address resolution program

by steve hanna v.01

vividmachines.com

shanna@uiuc.edu

you are free to modify this code

but please attribute me if you

change the code. bugfixes & additions

are welcome please email me!

to compile:

you will need a win32 compiler with

the win32 SDK

this program finds the absolute address

of a function in a specified DLL.

happy shellcoding!

***************************************/

int main(int argc, char*\* argv)

{

HMODULE hmod_libname;

FARPROC fprc_func;

printf("arwin - win32 address resolution program - by steve hanna - v.01\n");

if(argc < 3)

{

printf("%s <Library Name> <Function Name>\n",argv[0]);

exit(-1);

}

hmod_libname = LoadLibrary(argv[1]);

if(hmod_libname == NULL)

{

printf("Error: could not load library!\n");

exit(-1);

}

fprc_func = GetProcAddress(hmod_libname,argv[2]);

if(fprc_func == NULL)

{

printf("Error: could find the function in the library!\n");

exit(-1);

}

printf("%s is located at 0x%08x in %s\n",argv[2],(unsigned int)fprc_func,argv[1]);

}

Get the address of LoadLibraryA in kernel32.dll

Let’s take a break here and think a little further. Why exactly do we need LoadLibraryA? If you read the steps I wrote down back to front, you will realize what we want is the address of MessageBoxA. As we have seen, Win XP does not implement ASLR. So why did’t we just use arwin and hardcode it’s address?

Let’s read the following paragraph from this source:

In summary, we are interested in KERNEL32.DLL because it is:

guaranteed to exist in all processes

contains LoadLibrary() and GetProcAddress() APIs which unlock access to all other API functions

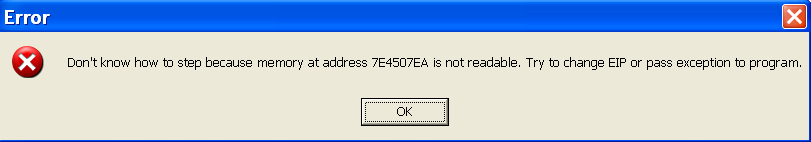

Hm, so we can take kernel32.dll for granted but we cannot guarantee user32.dll exists in this process. Indeed, if we skip it and hardcode the address of MessageBoxA, this is what might happen:

Right, this area of the memory (user32.dll) is not mapped into the program’s memory space. That is why we must load it first.

Now that we fully understand what we are doing, we simply use arwin for completing this step:

Load user32.dll using LoadLibraryA

This is where the fun begins. Let’s check MSDN and get the syntax of this function:

HMODULE LoadLibraryA(

LPCSTR lpLibFileName

);

Pretty straightforward. Here is what we are going to do in our debugger:

- Put the address of LoadLibraryA into a register (say EAX)

- Put the string “user32.dll” onto the stack

- Save the address of beginning of the string “user32.dll” into a register (say EBX)

- Push EBX (user32.dll)

- Call EAX (LoadLibraryA)

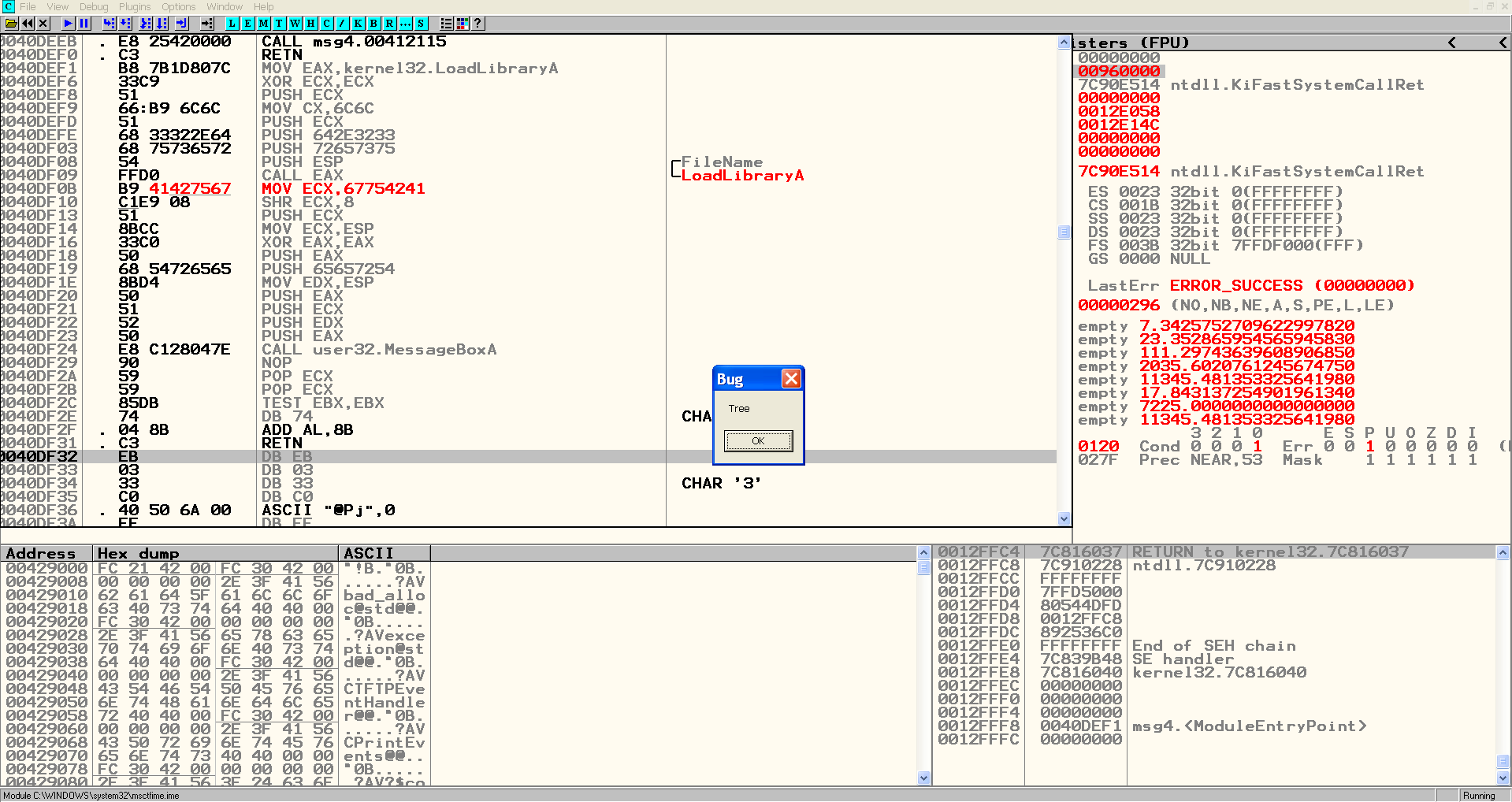

This is our assembly code for this part:

0040DEF1 > B8 7B1D807C MOV EAX,kernel32.LoadLibraryA

0040DEF6 33C9 XOR ECX,ECX

0040DEF8 51 PUSH ECX

0040DEF9 66:B9 6C6C MOV CX,6C6C

0040DEFD 51 PUSH ECX

0040DEFE 68 33322E64 PUSH 642E3233

0040DF03 68 75736572 PUSH 72657375

0040DF08 54 PUSH ESP ; /FileName

0040DF09 FFD0 CALL EAX ; \LoadLibraryA

You can load any binary into your favorite debugger and press SPACE to edit the current instruction.

The first line directly corresponds to step number 1. Lines 2 to 4 correspond to step number 2. Now, this is a little trickier than it might seem at first. Whenever we push stuff onto the stack, it must be in blocks of 4 bytes (32 bits). There are two caveats here, however:

- The string must end up with a NULL byte

- The order of the blocks

To solve the first point, we push a NULL double word onto the stack. Since \x00 is a common badchar, we avoid it by zeroing ECX with XOR ECX, ECX and then pushing ECX.

Now, for the second point, our string user32.dll gets divided into user, 32.d and ll. Since this last block is composed only by 2 bytes, we do not push it directly, due to the fact that unwanted NULLs would be inserted in our shellcode. Instead, we first move 6C6C to CX, which is 2-bytes long, and then push CX.

Get the address of MessageBoxA in user32.dll

Now that user32.dll is loaded into the memory space, we can use arwin to retrieve the address of MessageBoxA, which, as we have already seen, 0x7e4507ea.

Put parameters on the stack

This step will be similar to step 2, just with a few more parameters. Fire up MSDN and check the syntax of MessageBoxA:

int MessageBoxA(

HWND hWnd,

LPCSTR lpText,

LPCSTR lpCaption,

UINT uType

);

Just remember those 2 points from step 2: the NULL byte and the 4-bytes block order. If you read the documentation (please do), you will know that both uType and hWnd might be zero. For lpCaption, we will push “Bug” and for lpText, we will push “Tree”.

However, “Bug” has only 3 bytes. As we are dealing with a 32 bits stack, we cannot push 1 byte. Because of this we cannot split “Bug” into “B” and “ug” and use the same trick as we did in step 2. Another solution would be to use a shift.

The instruction SHR allows us to rotate an operand a certain number of bits to the right. We can use it to complete our task:

MOV ECX,67754241 ;guBA

SHR ECX,8 ;ECX=00guB

PUSH ECX

We added a random character to our string (“A” in this case) and then shifted the whole thing to the right. This solution is also interesting because we could also insert the NULL byte we need at the end of the string!

This step then becomes:

0040DF0B B9 41427567 MOV ECX,67754241

0040DF10 C1E9 08 SHR ECX,8

0040DF13 51 PUSH ECX

0040DF14 8BCC MOV ECX,ESP

0040DF16 33C0 XOR EAX,EAX

0040DF18 50 PUSH EAX

0040DF19 68 54726565 PUSH 65657254

0040DF1E 8BD4 MOV EDX,ESP

0040DF20 50 PUSH EAX

0040DF21 51 PUSH ECX

0040DF22 52 PUSH EDX

0040DF23 50 PUSH EAX

Call MessageBoxA

Finally, we just call the address of MessageBoxA. Do notice however that we are using E8 as an opcode, so it means:

Call near, relative, displacement relative to next instruction.

In some other cases you might need to move the address to a register and then call it. If you have no idea of what I am talking about, take a look at this.

0040DF24 E8 C128047E CALL 7E4507EA

Putting it all together

Putting the three previous steps together we have the final shellcode

0040DEF1 > B8 7B1D807C MOV EAX,kernel32.LoadLibraryA

0040DEF6 33C9 XOR ECX,ECX

0040DEF8 51 PUSH ECX

0040DEF9 66:B9 6C6C MOV CX,6C6C

0040DEFD 51 PUSH ECX

0040DEFE 68 33322E64 PUSH 642E3233

0040DF03 68 75736572 PUSH 72657375

0040DF08 54 PUSH ESP ; /FileName

0040DF09 FFD0 CALL EAX ; \LoadLibraryA

0040DF0B B9 41427567 MOV ECX,67754241

0040DF10 C1E9 08 SHR ECX,8

0040DF13 51 PUSH ECX

0040DF14 8BCC MOV ECX,ESP

0040DF16 33C0 XOR EAX,EAX

0040DF18 50 PUSH EAX

0040DF19 68 54726565 PUSH 65657254

0040DF1E 8BD4 MOV EDX,ESP

0040DF20 50 PUSH EAX

0040DF21 51 PUSH ECX

0040DF22 52 PUSH EDX

0040DF23 50 PUSH EAX

0040DF24 E8 C128047E CALL 7E4507EA